Over my time at the University of Utah, I look back and understand that we never could have helped $400 billion in pension funds to reimagine how they do what they do without many helping hands along the way. Among those people were Danny Wall, Mark Parker, and Taylor Randall. I state those individuals in order, Danny, assistant dean over specialized programs was my “ground support,” while Mark , graduate programs associate dean was the oversight and “air support,” and at the highest level Taylor, the dean, provided freedom to get the things done right. I think all three men were necessary for the success and I am happy for the experience we had helping students and pension funds.

At this point I also look back on some the biggest successes I know of in finance and how they were done, and in short, they were always accomplished with small groups of people with proper leadership providing the same kind of “on the ground” and “in the air” support that I got at the University of Utah. I know this from personal experience and from interaction with my friends who have led transformative technology efforts. I will relate three experiences in the next three weeks, starting with that of Barr Rosenberg who helped implement computerized investment systems that changed the entire investment industry. The amazing thing about these efforts is that they were always done by very small groups, the proverbial a “couple of guys in a garage” with a couple of main supporters outside the garage.

Hal Arbit and American National Bank (ANB)

American National Bank (ANB) in Chicago was known for being one of the nation’s most innovative banks. Among it’s bold experiments, it’s CEO had a vision of making it the first bank in the United States with fully computerized investment operations. To fulfill this mission the CEO hired Hal Arbit, an innovator in the field of the practical application of computerized concepts to the financial industry. Arbit hired numerous quantitative savvy employees, such as Jack Treynor and Rex Senquefield, but as significant as the internal operations were at ANB, they reached an entirely new level when Arbit hired Barr Rosenberg and a small group of consultants out of Berkeley, California.

Barr Rosenberg was an accomplished academic, but more importantly Arbit recognized Rosenberg as a talented systems architect and hired Barr to review and completely rework ANB’s entire computer systems. This rebuild was not just limited to portfolio management and risk, but extended to reconciliation, trading, and research. While Barr and his team worked day to day to rebuild the systems, Arbit provided the “air cover” to get the job done. Finally, after three years, the complete system was done that would change the investment world. It was so complete that it had over 1,000 pages of documentation, but it handled everything automatically in the investment process. More importantly, two people were the primary programmers, in marked contrast to much larger groups from companies such as IBM that had proved not able to accomplish the task.

Among the things that computerized system allowed, was for ANB to produce the world’s index fund, an S&P 500 fund that rose to over $12 billion AUM due to the low cost that the completely computerized systems allowed. This was extremely difficult at the time because the high transaction costs and low liquidity of smaller cap stocks made it so the only way to reasonably do this was to produce a sophisticated statistical arbitrage fund. Huge stat arb funds at companies such as Morgan Stanley and DE Shaw were later build on this very principal, and Barr was delivering it in a working trading system! The systems were literally decades ahead of the competition, but as often happens with such innovation, it ran into a road block.

Just as all of ANB was to be remade by the new quantitative systems, new leadership took the helm at ANB and decided to scrap the entire “quant effort” because they saw easier money in financing leveraged buyouts. This move eventually led to ANB’s bankruptcy, but before that there was an exodus of quantitative talent, all armed with the innovations developed at ANB. These people founded companies and stocked quant departments at firms as Wells Fargo and Mellon Bank. As for Arbit, he quit ANB and moved to California to see where the quantitative innovations would take them.

James Vertin and the Wells Fargo Win

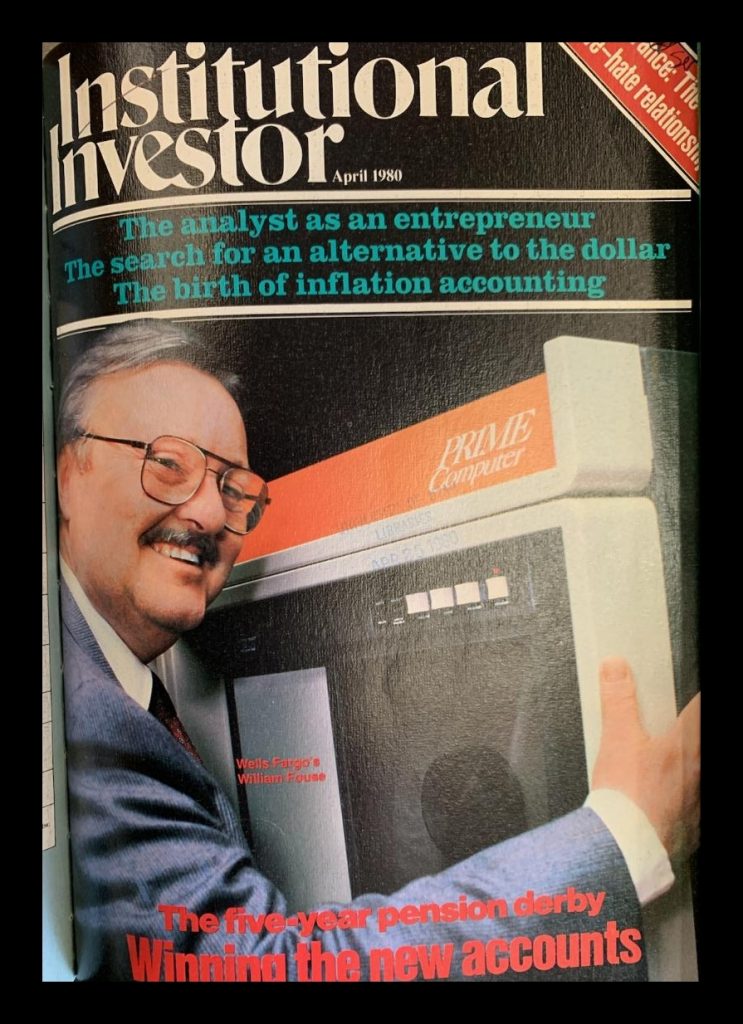

With ANB abandoning its quant efforts, Barr Rosenberg and his team was recruited to work with Wells Fargo, another company that had decided to go down the computerization route having been induced to do so by a “$1 million offer” by IBM to computerize their investment systems. Years later, having spent significantly more than $1 million on the effort, James Vertin, engaged Barr and his small group to do what they’d done at ANB. This time the CEO fully supported the effort. Barr and his team joined and the magazine cover below is the result. Within two years Wells Fargo was a powerhouse, setting the stage for it to become the largest investment manager in the world. Incidentally, that group still holds the crown of being the biggest institutional investor to this day, now called “Blackrock Scientific.”

As for Arbit, he set up shop in Northern California and with his former employee Jack Treynor and helped back the quant revolution, including several companies that IPO’d or were sold, including three by Barr Rosenberg.

Picking the Right Partners means the Right People

Many people focus on picking the right company to partner with, but as the case of American National Bank and Hal Arbit demonstrates, it is much more about the right people than the right company. Even the largest companies can make incorrect decisions and go out of business as ANB did, but the right people like Hal Arbit and James Vertin will see transformative projects through to the end, sometimes even being there after the IPO. In this sense, much of the innovation that the financial system is in so dire need is a function not only about the entrepreneurs that bring new technologies to market, but about the bold people who can understand and back those new technologies.