Dan Bricklin is a Loser

Some months ago, I had an investment banker tell me that “Dan Bricklin is a loser!” He told me that he had met Bricklin at a Vermont ski resort and that Bricklin was a loser because, while he was “the first,” he didn’t keep control of his invention. He said it didn’t matter being first, or in other words, innovation didn’t matter. To put this in context, Dan Bricklin is commonly credited as the creator of the modern spreadsheet, Apple’s first “killer App“—a program called VisiCalc. To put this conversation in further context, the man calling him a loser was a Harvard MBA on the McKinsey team that convinced Time Warner to “purchase” AOL in what is considered one of the worst corporate mergers in history. This “winner” got a job at one of the investment banks that reaped hefty fees from the ill-fated merger. People like this do not know what value is but instead confuse it with the price, something Ben Graham said should be thought of as more of a voting machine than a scale.

Dan Bricklin is a Winner

Dan Bricklin is indeed one of the most important software engineers in modern history and one of my heroes. He took a mainframe specification and turned it into a useful program that decentralized analysis and allowed Apple to rise and the PC age to mature. Amazingly, Dan did this when pursuing his Harvard MBA, a wonderful thing that such an amazing technology sprang from a business school. Investment bankers like the aforementioned “winner” are more typical of what is produced by MBA programs. These people follow well-worn trails in pursuit of price rather than blazing paths of innovation that lead to lasting value. No, among the engineers and innovators I deal with, Dan Bricklin is a winner, and the former is a loser or in the least lost pursuing a path with the rest of the crowd, not knowing where it leads.

Madness of the Crowds

So much for the wisdom of the crowds. Something particularly relevant when you have companies like Snowflake with inferior technology and no clear path to significant profitability trading at close to $90 billion. My friends actually in the know have described such circumstances as leading to “the biggest short opportunities in history.” they seem to forget the $100 billion AOL writedown for Time Warner, the fact that over 98% of game and then internet companies went bust, the Housing Bubble that triggered the 2008 Financial Crisis, and all the other bubbles we’ve lived through. Madness trumps wisdom in the short term and the markets can continue to be crazy longer than any individual can outlast them, something the hedgies betting against Gamestop have discovered. Madness or wisdom, bankers continue to bank and stoke the fire, but this bubble will burst at some point. At this point, I’d like to turn to another winner with a Harvard MBA—Clayton Christensen.

Clayton Christensen is a Winner, and so are the Innovators he studied

Many years ago, a young man from Salt Lake City entered Harvard Business School with a vision of changing the world via new technologies. He graduated and went on to great things, eventually starting a technology business that he ran as CEO. That business did not become the next IBM or Google but instead failed because of “freshmen” choices. He described one of the biggest as choosing a key executive because he had a great resume and were what his VCs wanted and not selecting the person with hard-fought, hands-on experience that his gut told him was right. A “loser,” he came back to Harvard to consult with his mentors, who advised him to come back to Harvard to apply the lessons he’d learned and study innovation. He finally graduated at 40, an advanced age for a recent Ph.D. graduate, and then began to evangelize technological innovation and came to become the most respected and admired consultant in Silicon Valley. That former “loser” was Clayton Christensen, and what made him a winner was he learned from his mistakes and then focused on something of value.

How to Measure Your Life

One of my best friends in college had the distinct pleasure of teaching at Harvard with “Clay” and becoming his protégé. I, in turn, had the joy of observing this all from afar. After spending years as the most respected consultant in the world, Clayton Christensen began to succumb to a terminal illness. Wanting to memorialize the counsel, the Harvard administration asked him to give a “Last Lecture” to one of their graduating MBA classes. That sermon was embedded in his book How Will You Measure Your Life? Solid advice explaining that some apparent winners like his classmates who started Enron did not measure up even to the own standards as they pursued price mercilessly the whole while never delivering value. In other words, they valued themselves by a voting-machine and not a scale. Ultimately this is what I believe. We measure ourselves as we look in the mirror every day, and those that measure up, such as Dan Bricklin and Clayton Christensen, have pursued value and are people of value.

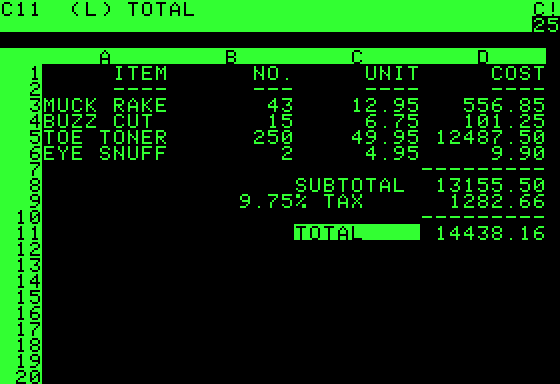

Innovation doesn’t come from Big Banks

One obvious thing Clayton Christensen observed is that innovation does not typically come from the established players—they simply have too much to lose. That’s why when massive trading innovations were to be implemented, the investment bankers lost out. Those innovations resulted in 98% of existing traders losing their jobs. We are about ready for another such transformation resulting in financial information integration, our economy’s lifeblood, and the application of AI technologies like optimization. It is a dirty secret that our data-driven economy’s lifeblood is driven by armies of CPAs in low-cost centers such as India, all manually reconciling data on PC spreadsheets (thanks, Dan Bricklin). Then the best of the best mull over these decisions and go by their gut. Again, don’t expect the banks to be on the front lines for this innovation applying AI. While they use tools like those developed by Dan Bricklin, they infrequently go back to school as Clayton Christensen did. I’ve found that those refusing to go back to school and learn often get schooled by the harsh realities of life. Schools about ready to get in session!

P.S.

The following magazine cover relates to an article written by one of Clayton Christensen’s former students who had reviewed the general nature of financial and, in particular, investment technology. Life can indeed be a harsh teacher to people swimming of their depth in the Blue Ocean, a dangerous place to be when you don’t know how to innovate or even recognize it. Even more so when you’re a tuna that thinks its a shark. A red ocean will naturally follow.