So it’s April Fool’s day, so I’d like to start this entry with a question, “What do a peace-loving philosopher, a Nazi-trained engineer, and a Buddhist Monk have in common?” The answer is that they were the fathers of the next stage of investment FinTech that occurred at Berkeley, California. To understand this, we must go back to the foundational work done in Colorado.

Berzerkeley and Strange Bedfellows

All the groundwork accomplished in Colorado in establishing econometrics as the language of analysis, providing the first computerized dataset on which systematic analysis could be performed and the related development of the first “alpha mining” engine set the stage for something completely new to emerge out of Berkeley, California. My father, an environmental crusader and billboard executive (two things that typically don’t go together), graduated with his Ph.D. from Berkeley so I’m well aware of the strange bedfellows and hybrids that emerge from the environment. That’s the whole reason that some people call it Berzerkeley. It’s also the reason that it’s so wonderful, often emulated, but never replicated. The main actors in this part of the development of the Silver Age of investment FinTech were the aforementioned characters, a set of “Three Amigos” led by a peace-loving philosopher who holds the distinction of being the only man that Noam Chomsky learned anything from as an undergraduate.

The peace-loving philosopher was C. West Churchman, a man who literally created the field of operations research as an academic discipline. Churchman was widely recognized as one of the most amazing and wide-ranging intellects at Berkeley—no small feat in those days. While his day job was creating the discipline of operations research, on the side he worked with NASA and had an eclectic set of interests that ranged from accounting scholars to world peace negotiations. Beyond all of this, he also was also one of the first people to have the idea of adapting optimizers to the investment process. What this meant to Churchman was that he would have to figure out how to create a system that would let him analyze stocks in two ways. First, he’d have to figure out how to determine the value of stocks. Second, he’d have to determine how to measure the risk of those same stocks. If Churchman could do this, he could set up an optimization problem that could automatically allocate capital, something he felt would be a great social good (yeah, an investment that has made trillions was done to allocate capital for social good).

The Emergence of Alpha and Beta

To solve the first problem (the one about valuation), Churchman turned to a curious German academic who had been publishing work out of Canada about the possibility of building a system that could automatically simulate a company. Intrigued with the German who’d received his Ph.D. under Nazi engineers in the waning days of World War II in Vienna, Churchman and his colleagues invited him to Berkeley starting their own version of Operation Paperclip. That man, Richard Mattessich, ran an open-source software project at Berkeley that not only gave the world the first systematic company valuation program (Harold Silver’s system was more of a signal-based system), but it also produced things such as the world’s first electronic spreadsheet. Of course, all of these systems utilized the S&P Compustat data as “fuel.” With this part of the project done, Churchman turned to risk or “beta.”

For those of you who don’t know, the idea of beta is a concept of risk as it relates to stocks. Beta gets its name from the coefficient of regression (there we go with econometrics) of a company’s returns as they relate to the market as a whole. The idea had caught on in the East, with financial engineers buying into various forms of what was referred to in the day as the Efficient Market Hypothesis. In essence, the assumption behind beta was that the only risk that really mattered was the risk of the market because that risk could not be diversified away. Suffice it to say that the idea was great in theory, but horrible when compared to reality. In other words, the idea of beta as defined by the top academics in finance just never worked in practice.

Buddhists and Bionic Betas

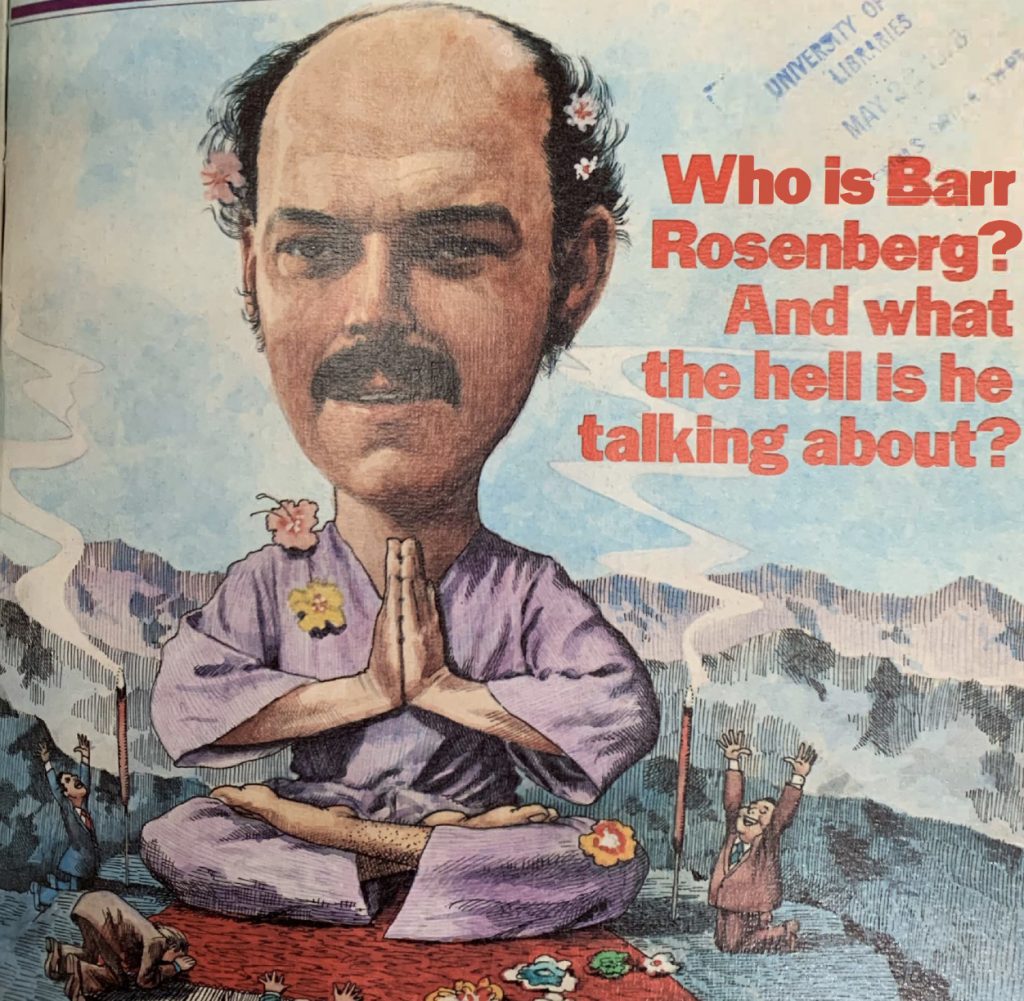

It was precisely because the concept of beta was so flawed, that Churchman and the National Science Foundation (NSF) stepped in. The NSF rarely takes much interest in economics (only 2% of its grants) and practically never in finance, but it revered Churchman, and based upon his advice they searched out the best young econometrician they could find to address the “beta problem.” That econometrician was Barr Rosenberg, at the time a young professor at Berkeley and, yes, he’s the Buddhist monk.

Choosing Barr was a roaring success, so much so that Barr became a “cover boy” and cult-like celebrity in Finance for several years. I actually spoke to a researcher at the NSF who keeps track of the economic impact of their funding and he said it was the “best bet” they ever made in economics. Here’s a copy of his first cover on Institutional Investor magazine indicating both his Barr’s Berzerkeley cred and the importance of the “cult of Barr” in the investment world. This was from 1978, far from the flower child days of the 60’s.

Bionic Betas and the Bishop

The first thing that Barr did when addressing the beta problem was to improve his econometric techniques, which allowed him to vastly improve his estimates of beta and get them closer to representing risk in the market. Not to be stopped there, Barr started to incorporate information from S&P Compustat into his calculations, and sure enough, the beta estimates improved again. These super betas started to be called “Barr’s Bionic Betas” and soon everyone wanted them. Barr established a company called Barra (for Barr Associates, now a part of MSCI) and he then started delivering his bionic betas out of his garage. Over time he shed the academic rigidity about relating everything just to beta, and he started delivering a whole set of measures of risk that he termed “risk factors,” with most being related to the underlying S&P or market data.

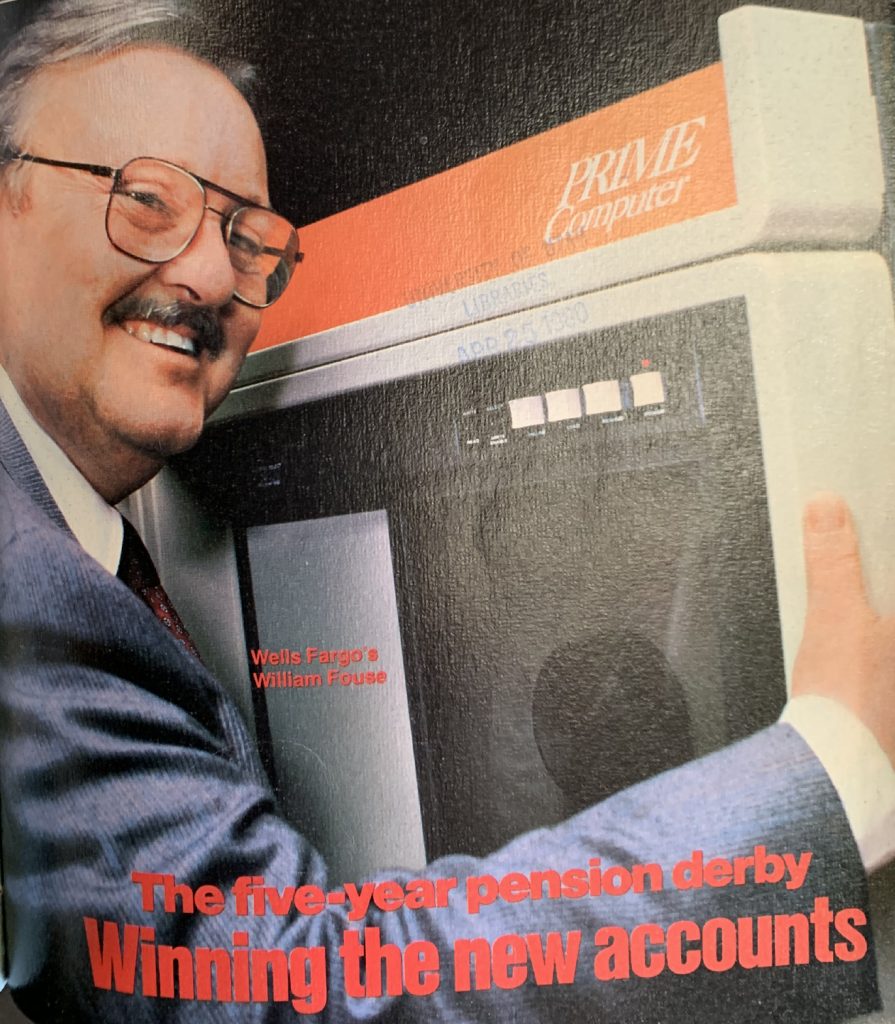

Barr didn’t stop at risk, his company soon worked with clients such as Wells Fargo’s Investment Trust, whose success in applying his risk methods and Churchman’s optimization routines led them to start building investment systems that curiously looked a lot like the early routines Harold Silver had done in Denver with Compustat and a set of brokers like Merrill Lynch. The man that worked with Barr in replicating and improving these systems was none other than Bill Fouse. Barr worked so closely with Bill that they called Barr the Pope (is the Pope Buddhist?) and Bill the Bishop. Here’s the Bishop on his own cover of Institutional Investor magazine just a couple of years after everyone was asking what the hell Barr was talking about.

Wells Fargo and the Rise of Quantitative Investing

As the cover story says, “Winning the New Accounts” and nothing gets copied faster than success in investment management. Within just a few years, Wells Fargo became the largest institutional investor in the world (it is now Blackrock Scientific) and their success in implementing the risk control tools just further fueled the frenzy. Barr followed his risk and investment products, with trading systems and operations systems, something that Churchman had envisioned when the whole project started. A famous quote by Churchman as the Berzerkeley finance revolution began was:

“How can we design improvement in large systems without understanding the whole system, and if the answer is we cannot, how is it possible to understand the whole system?”

C West Churchman, Challenge to Reason (1968)

In other words, Churchman knew that they’d have to eventually address everything if they wanted to rebuild finance around quantitative systems. Amazingly this quote remains prescient and in force to this day. In the exceptions of certain large quantitative hedge funds that have built all of their own integrated domain-systems, the majority of investment systems are still based on the work done in Berkeley in those few years. For example, about 70% of the world’s assets are managed by Barr’s risk models (today it’s known as MSCI Barra). Furthermore, about 70% of trading algorithms used today go back to work Barr and company did with a joint-venture with Jefferies and later spun-out into a public company (investment Technology Group (ITG)). It doesn’t end there, because the broker data collection system pioneered by Harold Silver and perfected by “Barr and Bill” is still in effect in pretty much in the same form (actually a little worse) with the most dominant broker data set (now known as IBES).

Just as the work in Colorado had established the foundation for work done in Berkeley, so would New York take the Berkeley innovations to the next level.