An early result demonstrating the importance of a proper process of integrating human and machine intelligence was presented to the world by one of my all-time heroes, Homer Warner, who I first heard about from Dr. Robert Koler, a mentor of mine when I was in high school.

The Genesis of the HELP Program

Dr. Koler and I were discussing the proper way to integrate computer science (my area) with genetics data, tools, and researchers (his area). During our first discussion, he directed me to examine work done by the LDS Hospital/University of Utah’s Dr. Homer Warner. Much of this work in the early years was centered around HELP (Health Evaluation thru Logical Processing), a program he wrote and maintained. Started before I was born, HELP was the first computer program that used medical records to conduct logical evaluations of suggested courses of treatment and it was good right out of the gate. The first version was done before computers were even digital (see the picture below). However, despite the program’s clear improvement upon normal human diagnosis, it was not seamless in its adoption in the medical community.

Initially, the program did not have such a friendly name as the objective was instead to simply have the program running in a backroom telling doctors what to do with their cardiac patients. It had been funded by a big National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant to quite a bit of local fanfare that it could give a more accurate cardiac diagnosis than the average doctor, assuming that it got accurate data. As a result of the importance of the data to the program, doctors and nurses here trained and were directed to feed it information. As it turned out, that was a problem because the data from the humans seemed to regularly have simple problems (as it turns out, a common thing that occurs when implementing new systems is that people think the system will replace them), so Dr. Warner then went about developing medical devices that could record information more accurately than human beings. While this work formed the foundations of a multi-billion-dollar medical devices industry in Utah, it did not result in better healthcare outcomes. Examining this, Dr. Warner found that despite the program’s accuracy, doctors simply didn’t trust it and as a result, they wouldn’t use its directives.

Suggestions, not Directives

Looking into the problem, Dr. Warner found that doctors simply did not like being told what to do by a computer, and they simply could not believe that it was more accurate than them. Dr. Warner knew that the long-term improvement, and evolution, of the program would only occur if people actually used the program and so he set out to improve the program and make it more “usable.” One of the most important things he did in this process was to rebrand the product, hence its friendly name “HELP.” It was actually a full two years later when the backronym for HELP was settled on, the important thing for the name was to convey that the program was there to “help” doctors. Sure enough, when the information was presented as a suggestion and not a directive, the doctors all started to use HELP and as Dr. Warner and his staff took the input from the use of HELP, they found that the doctors who learned to use HELP effectively began to do better and better, but even more importantly these “forward adopters” started to perform better using help as suggestions than HELP could do alone.

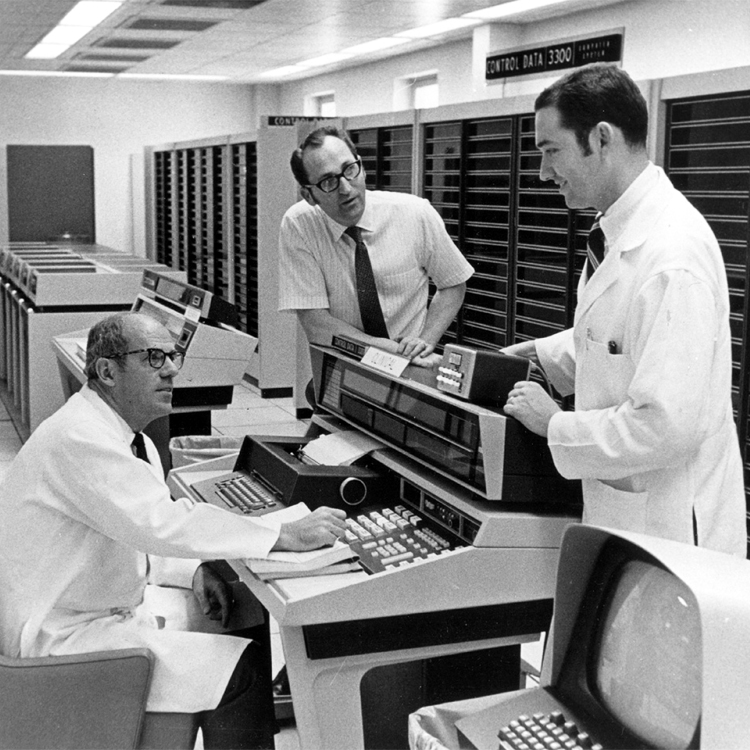

As the success of HELP grew, it expanded in its sophistication and scope, coming out of the back office, to fully integrate with the teams of doctors using it. Rather than limit the data, the doctors now looked for ways to enter additional information into HELP, including demographic information, historical medical records, and certain more “subjective” clinical observations. As more doctors used it, the scope of HELP increased, covering more maladies, suggested courses of action, and interactions in effect facilitating doctors as high value-added “medical strategists” with HELP taking over the routine “tactical analysis.” This is pretty much the same thing Kasparov found years later looking to hybrid Chess tournaments, but with HELP the stakes were much higher.

Over the years as HELP became more sophisticated, it utilized and integrated information from multiple diagnostic departments, not just giving suggestions, but integrating with pharmacies and operating floors to make sure that the wrong drug was not given to patients or the wrong procedure was not done. HELP was eventually sold to 3M forming the basis of an entirely new division, and it was shortly thereafter that Dr. Warner moved to the University of Utah to build the next generation system and train the next generation of doctors, all of whom would “grow-up” with the right tools. The biggest problem they had when Dr. Warner came to the University of Utah was what department to put him in, Medicine or Engineering. In a compromise, they created the first Medical Informatics Department, something that was soon copied by other universities, such as Columbia.

The University of Utah, the Iliad System, and Teaching the Next Generation of Medical Strategists

At the University of Utah, Dr. Warner and his team developed ILIAD, a computer program that used probabilistic and rule-based diagnoses to help train students and conduct medical testing. The Iliad System was written in C and developed over decades, consisting of an “inference engine” (a collection of rules and procedures for making decisions) and a knowledge base (a collection of medical facts and relationships). Iliad acted in three modes: consultation, simulation, and simulation-test. It was an amazing accomplishment for its time. While it used early versions of “artificial intelligence” or machine learning, the main thing distinguishing both HELP and ILIAD was that they were built around users and patients and they were unmitigated successes.

Dr. Warner was my hero for several reasons, among those most important were than he was always a student, always looking to improve his systems via user and patient input and via new advances in other areas. There are many stories here in Utah about his insatiable curiosity, whether it be about staying up all night studying Fourier analysis or transfer functions and applying them to his medical problems the very next day, or simply being the first person in the state to own an iPhone, he was always on the forefront and looking for new methods, processes and technologies to apply to the crucial problems he sought to address, which are by definition the problems that afflict us all.

Cross-disciplinary Collaboration is the Future

My main point here is that rather than trying to reinvent the wheel because it “sounds good,” we should be inspired by the pioneering work of men like Dr. Homer Warner who in many ways were decades ahead of us in finance. But as my friend Lee Hood conveyed to me (more on that later), we also have things to offer other areas from finance. Accordingly, we should have the humility to look to other fields, and the graciousness to share so we can ensure that we are all using the best methods, processes, and technologies. This was the idea that I had inculcated in me from my grandfather and Dr. Koler, two of my greatest mentors. It carried through at BYU, where I worked with statisticians in the NeXT lab, and at Columbia where I was the first person in the business school with a computer science Ph.D. on my dissertation committee.

That cross-disciplinary thinking permeates the ULISSES Project and is in the DNA of the University of Utah as demonstrated by Homer Warner’s own Odyssey. I close by relating a meeting that Mark Parker, the Associate Dean at the Eccles school, and a math Ph.D./optimization expert, and I had with Michael Young a few weeks ago. Michael is the new Director of the University of Utah Entertainment Arts & Engineering Program (a.k.a, “The Games Program”). Michael got his Ph.D. at the University of Pittsburgh in Intelligent Systems and as he stated to me in the meeting, his Ph.D. from the very beginning was cross-disciplinary. The discussion was about getting Games, one of the best programs of its type in the world, involved with the ULISSES Project, and in short, we all couldn’t think of anything more logical.

Expect great things in the future as we move forward with this historic collaboration.

2 Replies to “Artificial and Augmented Intelligence, Part 3 – Homer, HELP, and the Iliad System”