In grad school, I was running my own server room at my co-op thanks to a NeXT/Apple-related consulting project, and in addition to the money that the contract brought, it also generated additional consulting work. When people heard about what I was doing, I’d get offers from senior people in companies such as Morgan Stanley, Oppenheimer, and Prudential to be their “right-hand man” to implement new technology in their firms. While I liked the people, I realized that they weren’t even familiar with fundamentals about the technology that they were trying to deploy, so in each case, I would do a bit of consulting, but when pushed to join them full time, I had a standard refrain that I was “going to be a professor.”

While I was always more interested in application than academia, I just hadn’t found the right group so I said I was going to be a professor simply because it had never “clicked,” but all that changed after meeting with the head of research of the largest investor in the world, Barclays Global Investors (BGI). It wasn’t as glamorous as it probably sounds. They were desperate and effectively going out of business…not exactly the kind of offer I thought I’d entertain, let alone accept but as it has been said, a crisis is a combination of danger and opportunity.

The BGI Rebuild

When I first started talking to BGI, they were going out of business because numerous hedge funds were front-running their models. Their “head of research” had never built an investment model, as all the early models and entire investment platform was built by Barr Rosenberg, with BGI just “iterating on the edges” since Barr’s days. While innovative in its day, It was so bad and universally panned then that when I went to the Q-Group in the summer I joined BGI, I had a dozen people ask why such an innovative young researcher was going to such a “dead place.” This wouldn’t have been a problem for me, but two of those people asking me the question were Nobel Prize winners–not exactly something to boost my confidence about joining BGI. That said, I had hit it off with the head of research and he’d promised me that I’d have carte blanche to implement the changes I suggested. As strange as it was, it was the discussion about optimization that had gotten me to join the finance version of the baseball team in Major League.

The head of research was an OR Ph.D. from Berkeley who had worked for Barr as an optimization expert and that pretty much says it all. While he knew a lot about optimization and risk models, he didn’t know how to build an investment model, something he’d never done. He was desperately looking for help from someone who knew more about the investment process than he did. His search did not start with me, but rather my Department Chair who had done groundbreaking research on one of the first quantitative investment strategies, something called “post-earnings announcement drift.” This takes a lot to explain, but the simple point was that my Department Chair knew more about investment strategies than the head of research of the largest investment manager in the world.

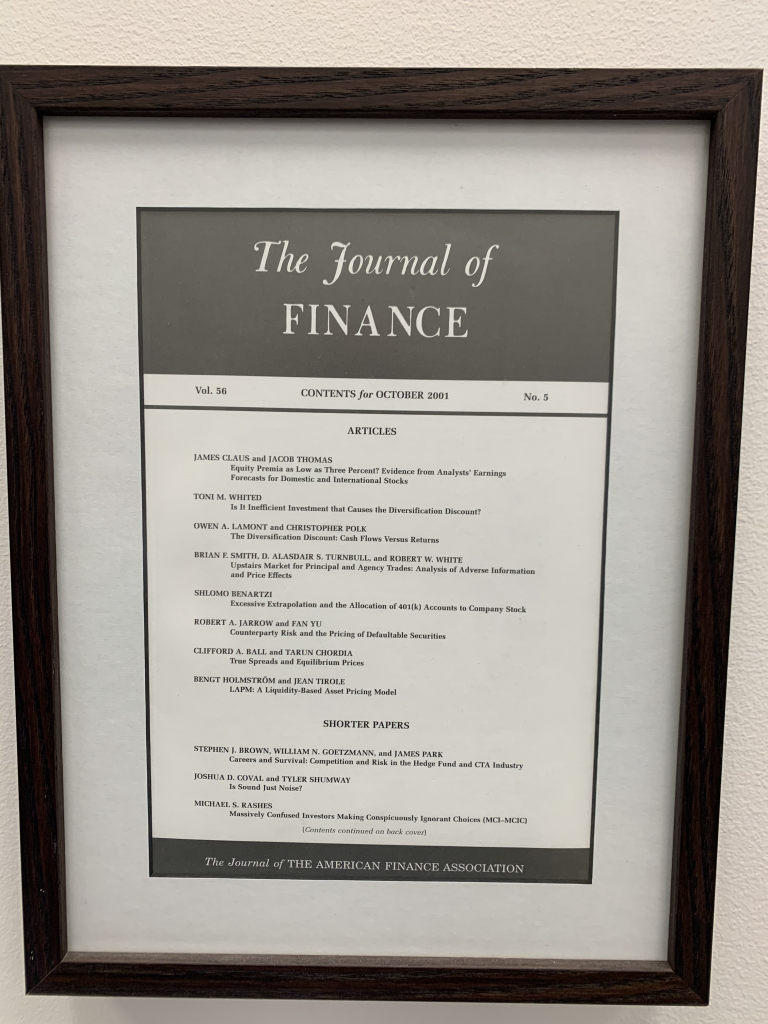

A More Advanced Black-Litterman Model

When Jake Thomas (the Chair) was called, it wasn’t about post-earnings announcement drift, which was not working anymore because the subsequent “Gold Rush” of firms replicating it “mined it out of the market,” ultimately leading to the strategy not working anymore. No, the immediate motivation for the call was a new paper that Jake and I wrote that showed even more promise than the first strategy, but you had to be clever enough to discern that we were talking about an investment model because academics didn’t believe you could beat the market and we had to hide this in the write-up. So instead of saying “here’s a macroeconomic investment strategy,” we discussed “the equity risk premium” in various countries.

While the head of research for BGI had not built an investment model, he could recognize one. He understood that what we did was “a more advanced version” of Fischer Black’s asset allocation program, something called the Black-Litterman model. He was, of course, right. I had used some optimization technology and some advanced time series econometrics to test the strategy so I was pretty sure that it worked, but I knew I couldn’t be sure if it didn’t run money.

Anyway, the head of research for BGI discussed the model with Jake and then asked him to join the firm to implement it. Jake said he wasn’t interested in joining BGI, and then the head of research moved on to his “grad assistant.” When he asked about me, Jake responded telling him I knew more about the markets than any student he’d ever worked with, but closed by saying “James is going to be a professor so I wouldn’t call him.”

Sniffing something of value, the head of research had a headhunter call me within the hour and set up a meeting the next day. At the time I was taking out my stress in a combination of powerlifting and open fighting (beyond Jiu-Jitsu) so I didn’t look like the average finance guy. I was told by the headhunter that when I arrived for lunch he was expecting “a smaller guy.” I smiled and said, “I’m the smallest of my brothers.” I was 6’0″ and 220 lbs at the time at reasonably low body fat. I later heard he described me to BGI as “High Finance meets World Wrestling Federation.” The guys from BGI were there in New York within days to meet me personally. The next week I was flown to San Francisco to spend the day with the head of research, the second most important person in the firm next to the CEO, and one of Barr Rosenberg’s former students.

The head of research was an optimization guy and it was a discussion around optimization that was the deciding factor for my decision to join BGI, but that discussion will have to wait till next week.